AV1 for video coding is what Opus is for audio coding.

The Alliance of Open Media (AOMedia) issued last week a press release announcing its public release of the AV1 specification.

Last time I wrote about AOMedia was over a year ago. AOMedia is a very interesting organization. Which got me to sit down with Alex Eleftheriadis, Chief Scientist and Co-founder of Vidyo, for a talk about AV1, AOMedia and the future of real time video codecs. It was really timely, as I’ve been meaning to write about AV1 at some point. The press release, and my chat with Alex pushed me towards this subject.

TL;DR:

- We are moving towards a future of royalty free video codecs

- This is due to the drastic changes in our industry in the last decade

- It won’t happen tomorrow, but we won’t be waiting too long either

Before you start, if you need to make a decision today on your video codec, then check out this free online mini video course

Now let’s start, shall we? 🙂

Table of contents

AOMedia and AV1 are the result of greed

When AOMedia was announced I was pleasantly surprised. It isn’t that apparent that the founding members of AOMedia would actually find the strength to put their differences aside for the greater good of the video coding industry.

Video codec royalties 101

You see, video codecs at that point in time was a profit center for companies. You invested in research around video coding with the main focus on inventing new patents that will be incorporated within video codecs that will then be globally used. The vendors adopting these video codecs would pay royalties.

With H.264, said royalties came with a cap – if you distributed above a certain number of devices that use H.264, you didn’t have to pay more. And the same scheme was put in place when it came to HEVC (H.265) – just with a higher cap.

Why do we need this cap?

- Companies want to cap their commitment and expense. In many cases, you don’t see direct revenue per device, so no cap means this it is harder to match with asymmetric business models and applications that scale today to hundreds of millions of users

- If a company needs to pay based on the number of devices they sell, then the one holding the patents and getting the payment for royalties knows that number exactly – something which is considered trade secret for many companies

So how much money did MPEG-LA took in?

Being a private company, this is hard to know. I’ve seen estimates of $10M-50M, as well as $17.5B on Quora. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle. Which is still a considerable amount of money that was funnelled to the patent owners.

With royalty revenues flowing in, is it any wonder that companies wanted more?

An interesting tidbit about this greed (or shall we say rightfulness) can be found in the Wikipedia page of VP8:

In February 2011, MPEG LA invited patent holders to identify patents that may be essential to VP8 in order to form a joint VP8 patent pool. As a result, in March the United States Department of Justice (DoJ) started an investigation into MPEG LA for its role in possibly attempting to stifle competition. In July 2011, MPEG LA announced that 12 patent holders had responded to its call to form a VP8 patent pool, without revealing the patents in question, and despite On2 having gone to great lengths to avoid such patents.

So… we have a licensing company whose members are after royalty payments on patents. They are blinded by the success of H.264 and its royalty scheme and payments, so they go after anything and everything that looks and smells like competition. And they are working towards maintaining their market position and revenue in the upcoming HEVC specification.

The HEVC/H.265 royalties mess

Leonardo Chiariglione, founder and chairman of MPEG, attests in a rather revealing post:

Good stories have an end, so the MPEG business model could not last forever. Over the years proprietary and “royalty free” products have emerged but have not been able to dent the success of MPEG standards. More importantly IP holders – often companies not interested in exploiting MPEG standards, so called Non Practicing Entities (NPE) – have become more and more aggressive in extracting value from their IP.

HEVC, being a new playing ground, meant that there were new patents to be had – new areas where companies could claim having IP. And MPEG-LA found itself one of many patent holder groups:

MPEG-LA indicated its wish to take home $0.2 per device using HEVC, with a high cap of around $25M.

HEVC Advance started with a ridiculously greedy target of $0.8 per device AND %0.5 of the gross margin of streaming services (unheard of at the time) – with no cap. It since rescinded, making things somewhat better. It did it a bit too late in the game though.

Velos Media spent money on a clean and positive website. Their Q&A indicate that they haven’t yet made a decision on royalties, caps and content royalties. Which gives great confidence to those wanting to use HEVC today.

And then there are the unaffiliated. Companies claiming patents related to HEVC who are not in any pool. And if you think they won’t be suing anyone then think again – Blackberry just sued Facebook for messaging related patents – easy to see them suing for HEVC patents in their current position. Who can blame them? They have been repeatedly sued by patent trolls in the past.

HEVC is said to be the next biggest thing in video coding. The successor of our aging H.264 technology. And yet, there’s too many unknowns about the true price of using it. Should one pay royalties to MPEG-LA, HEVC Advance and Velos Media or only one of them? Would paying royalties protect from patent litigation?

Is it even economically viable to use HEVC?

Yes. Apple has introduced HEVC in iOS 11 and iPhone X. My guess is that they are willing to pay the price as long as this keeps the headache and mess on the Android camp (I can’t see the vendors there coming to terms of who is the one in the value chain that will end up paying the royalties for it).

With such greed and uncertainty, a void was left. One that got filled by AOMedia and AV1.

Interested in more about this? Continue here ???? WebRTC & HEVC – how can you get these two to work together

AOMedia – The who’s who of our industry

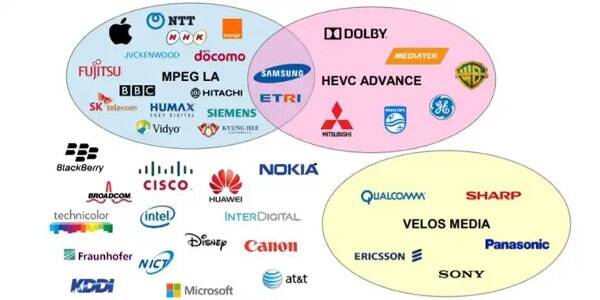

AOMedia is a who’s who list of our industry. It started small, with just 7 big names, and now has 12 founding members and 22 promoter members.

Some of these members are members of MPEG-LA or already have patents in HEVC and video coding. And this is important. Members of AOMedia effectively allow free access to essential patents in the implementation of AOMedia related specifications. I am sure there are restrictions applied here, but the intent is to have the codecs coming out of AOMedia royalty free.

A few interesting things to note about these members:

- All browser vendors are there: Google, Mozilla, Microsoft and Apple

- All large online streaming vendors are there: Google (=YouTube), Amazon and Netflix

- From that same streaming industry, we also have Hulu, Bitmovin and Videolan

- Most of the important chipset vendors are there: Intel, AMD, NVidia, Arm and Broadcom

- Facebook is there

- Of the enterprise video conferencing vendors we have Cisco, Vidyo and Polycom

- Qualcomm is missing

AOMedia is at a point that stopping it will be hard.

Here’s how AOMedia visualize its members’ products:

What’s in AV1?

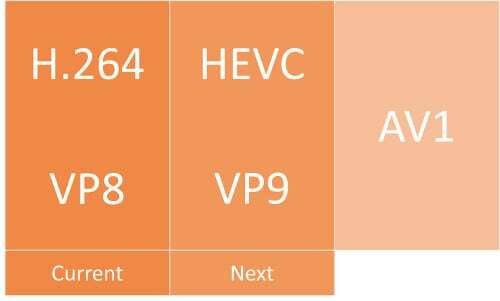

AV1 is a video codec specification, similar to VP8, H.264, VP9 codec and HEVC.

AV1 is built out of 3 main premises:

- Royalty free – what gets boiled into the specification is either based on patents of the members of AOMedia or uses techniques that aren’t patented. It doesn’t mean that companies can’t claim IP on AV1, but as far as the effort on developing AV1 goes, they aren’t knowingly letting in patents

- Open source reference implementation – AV1 comes with an open source implementation that you can take and start using. So it isn’t just a specification that you need to read and build with a codec from scratch

- Simple – similar to how WebRTC is way simpler than other real time media protocols, AV1 is designed to be simple

Simple probably needs a bit more elaboration here. It is probably the best news I heard from Alex about AV1.

Simplicity in AV1

You see, in standardization organizations, you’ll have competing vendors vying for an advantage on one another. I’ve been there during the glorious days of H.323 and 3G-324M. What happens there, is that companies come up with a suggestion. Oftentimes, they will have patents on that specific suggestion. So other vendors will try to block it from getting into the spec. Or at the very least delay it as much as they can. Another vendor will come up with a similar but different enough approach, with their own patents, of course. And now you’re in a deadlock – which one do you choose? Coalitions start emerging around each approach, with the end result being that both approaches will be accepted with some modifications and get added into the specification.

But do we really need both of these approaches? The more alternatives we have to do something similar, the more complex the end result. The more complex the end result, the harder it is to implement. The harder it is to implement, well… the closer it looks like HEVC.

Here’s the thing.

From what I understand, and I am not privy to the intricate details, but I’ve seen specifications in the past, and been part of making them happen, HEVC is your standard design-by-committee specification. HEVC was conceived by MPEG (jointly with VCEG, an ITU-T working group), which in the last 20 years have given us MPEG-2, H.264 and HEVC. Patents and royalties around these codecs were then handled by another group – MPEG-LA. The number of members in MPEG-LA with interests in getting some skin in this game is large and growing. I am sure that HEVC was a mess of a headache to contend with.

This is where AV1 diverges. I think there’s a lot less politics going on in AOMedia at the moment than in MPEG or MPEG-LA. Probably due to 2 main reasons:

- It is a newer organization, starting fresh. There’s politics there as there are multiple companies and many people, but since it is newer, the amount of politics involved will be lower than an organization that has been around for 20+ years

- There’s less money involved. No royalties means no pie to split between patent holders. So less fights about who gets his tools and techniques incorporated into the specification

The end result? The design is simpler, which makes for better implementations that are just easier to develop.

AV1 IRL

In real life, we’re yet to see if AV1 performs better than HEVC and in what ways.

Current estimates is that AV1 performance is equal or better than HEVC when it comes to real time. That’s because AV1 has better tools for similar computation load than what can be found in HEVC.

So… if you have all the time in the world to analyze the video and pick your tools, HEVC might end up with better compression quality, but for the most part, we can’t really wait that long when we encode video – unless we encode the latest movie coming out from Hollywood. For the rest of us, faster will be better, so AV1 wins.

The exact comparison isn’t there yet, but I was told that experiments done on the implementations of both AV1 and HEVC shows that AV1 is equal or better to HEVC.

Streaming, Real Time and SVC

There is something to be said about real time, which brings me back to WebRTC.

Real time low delay considerations of AV1 were discussed from the onset. There are many who focus on streaming and offline encoding of videos within AOMedia, like Netflix and Hulu. But some of the founding members are really interested in real time video coding – Google, Facebook, Cisco, Polycom and Vidyo to name a few.

Polycom and Vidyo are chairing the real time work group, and SVC is considered a first class citizen within AV1. It is being incorporated into the specification from the start, instead of being bolt-on into it as was done with H.264 and VP9.

Low bitrate

Then there’s the aspect of working at low bitrates.

With the newer codecs, you see a real desire to enhance the envelope. In many cases, this means increasing the resolution and frame rates a video codec supports.

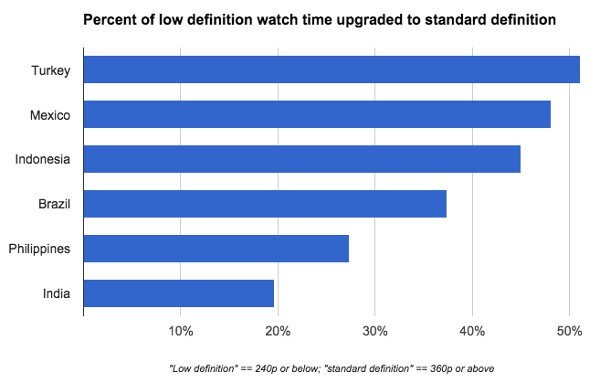

As far as I understand, there’s a lot of effort being put into AV1 in the other side of the scale – in working at low resolutions and doing that really well. This is important for Google for example, if you look at what they decided to share about VP9 on YouTube:

For YouTube, it isn’t only about 4K and UHD – it is on getting videos to be streamed everywhere.

Based on many of the projects I am involved with today, I can say that there are a lot of developers out there who don’t care too much about HD or 4K – they just want to get decent video being sent and that means VGA resolutions or even less. Being able to do that with lower bitrates is a boon.

Is AV1 “next gen”?

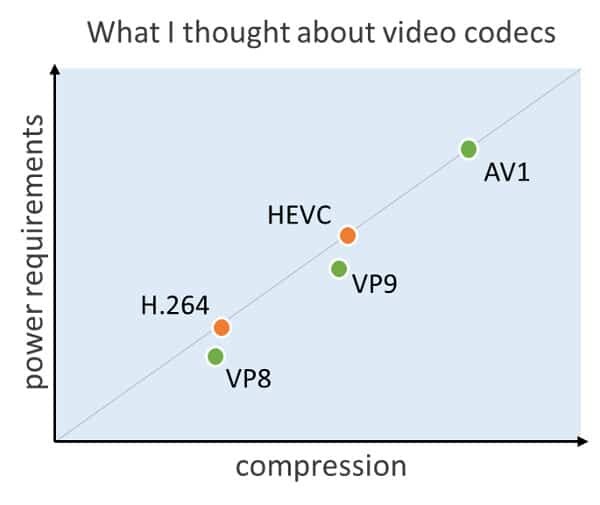

I have always considered AV1 to be the next next generation:

We have H.264 and VP8 as the current generation of video codecs, then HEVC and VP9 codec as the next generation, and then there’s AV1 as the next next generation.

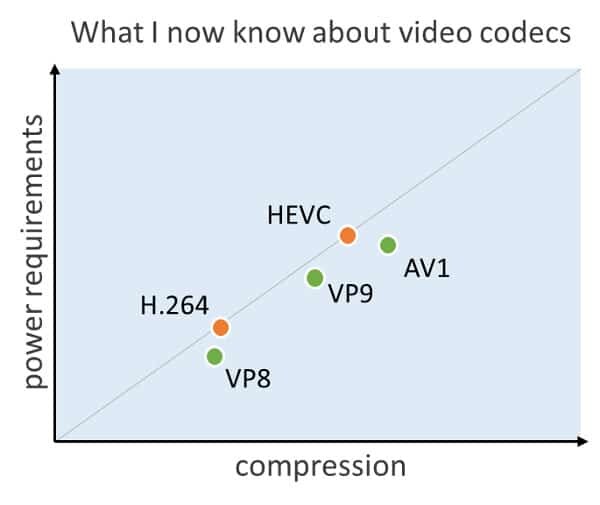

In my mind, this is what you’d get when it comes to compression vs power requirements:

Today though, I guess this would be closer to how I see things:

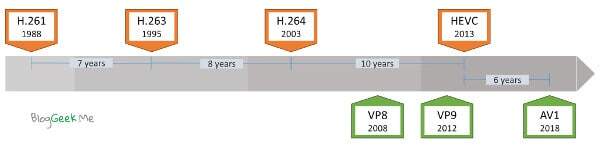

AV1 is an improvement over HEVC but probably isn’t a next generation video codec. And this is an advantage. When you start working on a new generation of a codec, the work necessary is long and arduous. Look at H.261, H.263, H.264 and HEVC codec generations:

Here are some interesting things that occurred to me while placing the video codecs on a timeline:

- The year indicated for each codec is the year in which an initial official release was published

- Understand that each video codec went through iterations of improvements, annexes, appendices and versions (HEVC already has 4 versions)

- It takes 7-10 from one version until the next one gets released. On the H.26x track, the number of years between versions has grown through time

- VP8 and VP9 have only 4 years between one and the other. It makes sense, as VP8 came late in the game, playing catch-up with H.264 and VP9 is timed nicely with HEVC

- AV1 comes only 6 years after HEVC. Not enough time for research breakthroughs that would suggest a brand new video codec generation, but probably enough to make improvements on HEVC and VP9

About the latest press release

AOMedia has been working towards this important milestone for quite some time – the 1.0 version specification of AV1.

The first thing I thought when seeing it is: they got there faster than WebRTC 1.0. WebRTC has been announced 6 years ago and we’re just about to have it announced (since 2015 that is). AOMedia started in 2015 and it now has its 1.0 ready.

The second one? I was interested in the quotes at the end of that release. They show the viewpoints of the various members involved.

- Amazon – great viewing experience

- Arm – bringing high-quality video to mobile and consumer markets

- Cisco – ongoing success of collaboration products and services

- Facebook – video being watched and shared online

- Google – future of media experiences consumers love to watch, upload and stream

- Intel – unmatched video quality and lower delivery costs across consumer and business devices as well as the cloud’s video delivery infrastructure

- NVIDIA – server-generated content to consumers. […] streaming video at a higher quality […] over networks with limited bandwidth

- Mozilla – making state-of-the-art video compression technology royalty-free and accessible to creators and consumers everywhere

- Netflix – better streaming quality

- Microsoft – empowering the media and entertainment industry

- Adobe – faster and higher resolution content is on its way at a lower cost to the consumer

- AMD – best media experiences for consumers

- Amlogic – watch more streaming media

- Argon Design – streaming media ecosystem

- Bitmovin – greater innovation in the way we watch content

- Broadcom – enhance the video experience across all forms of viewing

- Hulu – Improving streaming quality

- Ittiam Systems – the future of online video and video compression

- NGCodec – higher quality and more immersive video experiences

- Vidyo – solve the ongoing WebRTC browser fragmentation problem, and achieve universal video interoperability across all browsers and communication devices

- Xillinx – royalty-free video across the entire streaming media ecosystem

Apple decided not to share a quote in the press release.

Most of the quotes there are about media streaming, with only a few looking at collaboration and social. This somewhat saddens me when it comes from the likes of Broadcom.

I am glad to see Intel and Arm taking active roles. Both as founding members and in their quotes to the press release. It is bad that Qualcomm and Samsung aren’t here, but you can’t have it all.

I also think Vidyo are spot-on. More about that later.

What’s next for AOMedia?

There’s work to be done within AOMedia with AV1. This is but a first release. There are bound to be some updates to it in the coming year.

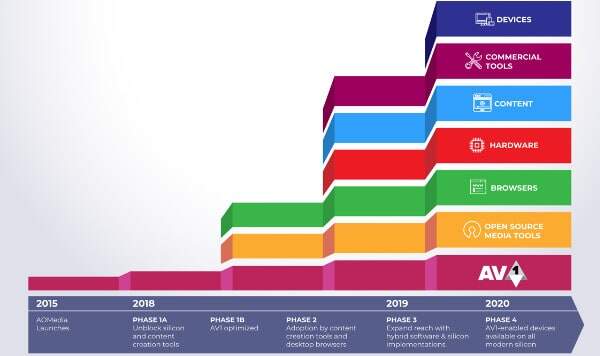

Current plans are to have some meaningful software implementation of AV1 encoder/decoder by the end of 2018, and somewhere during 2019 (end of most probably) have hardware implementations available. Here’s the announced timeline from AOMedia:

Rather ambitious.

Realistically, mass adoption would happen somewhere in 2020-2022. Until then, we’ll be chugging along with VP8/H.264 and fighting it out around HEVC and VP9.

There are talks about adding still image format based on the work done in AV1, which makes sense. It wouldn’t be farfetched to also incorporate future voice codecs into AOMedia. This organization has shown it can bring into it the industry leaders into a table and come up with royalty free codecs that benefit everyone.

AV1 and WebRTC

Will we see AV1 in WebRTC? Definitely.

When? Probably after WebRTC 1.0. Or maybe not 😉

It will take time, but the benefits are quite clear, which is what Alex of Vidyo alluded to in the quote given in the press release:

“solve the ongoing WebRTC browser fragmentation problem, and achieve universal video interoperability across all browsers and communication devices”

We’re still stuck in the challenge of which video codec to select in WebRTC applications.

- Should we go for VP8, just because everyone does, it is there and it is royalty free?

- Or should we opt for H.264, because Safari supports it, and it has better hardware support.

- Maybe we should go for using VP9 codec as it offers better quality, and “suffer” the computational hit that comes with it?

AV1 for video coding is what Opus is to audio coding. That article I’ve written in 2013? It is now becoming true for video. Once adoption of AV1 hits – and it will in the next 3-5 years, the dilemma of which video codec to select will be gone.

For now though, we are left with an HEVC vs AV1 dilemma for WebRTC.

Until then, check out this free mini course on how to select the video codec for your application

I think there is a confusion between MPEG (the standard committee) and MPEG-LA, the later having nothing to do with the former, even though they chose the most confusing name, possibly in purpose.

I think the second H264 in the drawings should be H265.

AV1 is already in Firefox (receiving-side and decoding only) with a demo available from bitmoving. The reference encoder is unfortunately too slow as-is today (less than 1fps) to be usable in real time.

I fixed the illustrations – thanks for catching that one

It is a long and detailed overview, which provides some interesting points to be considered. One of the problems with AV1 that it doesn’t have enough technological tools to perform better than HEVC, and it will not perform better – the AV1 bitstream is going to be frozen very soon. You can find recent detailed comparison results here: https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/embed_code/key/1H8zF9DZNLq3F1 . Regarding the future video coding technology it is definitely not AV1, since again it almost doesn’t have technological tools providing some added value over HEVC. The future video coding technology will come from the JVET standardization efforts – the Joint Video Exploration Team on Future Video Coding of ITU-T VCEG and ISO/IEC MPEG. There is a lot of marketing standing behind AV1, but it just marketing – from the technological point of view the situation is very different.

Dan, I guess time will tell where the market will be headed.

From what I can see and feel, we’re on our way to royalty free video codecs.

“Royalty Free” is a very misleading definition – there is nothing royalty free today. AV1 supporters are using this definition to convince companies to join AOM, and it is quite bad that many companies do not understand what this term “royalty free” really means.

I must say, FUD is the best way of fluttery in technology.

Dan, AOM today includes Google, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Cisco, Mozilla, Intel, ARM, nVIDIA and many others. You sure they were misled and don’t understand the meaning?

While at it, can you explain what this term “royalty free” really means, and how it is different for AV1 versus VP8?

Your study appears to refer to a version of AV1 from around nine months ago, before a lot of the experiments had been locked down. I’m not sure how much this matters, but the visual comparisons I’ve seen suggest there have been improvements since then.

As the owner of a site with user-submitted content sites where video is a necessary part of our offering, but not “core”, I don’t want to be worrying about compatibility or transcoding, let alone licensing requirements. We’re looking to transition from AVC and SWF, not HEVC; image quality or size savings are great, but what really matters is whether our audience can play what’s uploaded.

Being able to just say “if you don’t see this, upgrade your browser” would be a huge win. Then we can perhaps stop thinking about it for another decade. With AV1’s partners, I see that being feasible by 2019; for HEVC, we’ve already been waiting for years. It’s kinda like GIF vs. APNG – might be “better”, but what matters is “working”.

There is a clear hit in this video that apple is going to support other codec. My believe it’s AV1. This video was recorded before the announcement of Apple joining the Alliance of Open Media.

https://youtu.be/4gG5HXVOByY?t=1m51s

The next thing they will work on AV1 is the codec speed. So it wil be usable with webRTC. They think they can make it work for webrtc.

https://youtu.be/9IY3OTTR7lM?t=22m38s

But still a few years before the adoption is there.

Excellent piece, Tsahi.

The pessimist in me fears that some NPE/patent troll will come along — preferably after the codec has been implemented — and spoil the party with patent claims.

The defensive patent pool is rather large… I don’t think it leaves much breathing room for patent trolls to attack without exposing themselves to counter suits from the AV1 supporters.

Hi,

Thabk you for very comprehensive information regarding AV1. But I don’t agree with your argument why AV1 will better than HEVC body where people wants there proposal get adopted in standard so that they get royalty. I think other way around because people will do more research and hard work so that their proposal get adopted and they get benefited in terms of royalties. Even small companies will try to have their patents inside the standard. Here in AV1 I think few companies will put their dedicated workforce who have their inherent interest but rest of companies may not have motivation except using it in future.

Vijay,

Time will tell.

The fact that even huge corporations like Microsoft and Amazon are involved in the development and implementation of AV1 seems to indicate the opposite of what you are saying. They see the bigger picture that making a more widely accessible (royalty free, open) codec means that they can pump more information more efficiently to all of their customers. It contributes to the overall ecosystem of the net and they all stand to benefit from that.

Kevin,

Not sure how you got to the conclusion that I think AV1 won’t happen or will by royalty bearing. I believe we share the same views and mostly due to the same reasons.

There’s a critical mass of huge corporations and video experts behind AV1, which makes it the natural path towards the future of video coding at this stage.

Excellent read. Got me to subscribe.

Thanks for the kind words Matt!